Chords and chord progressions are the ingredients that give songs their harmonic richness. That is why songwriters and musicians of all stripes should familiarise themselves with the building blocks of chords and their inversions. This aspect of music theory is both essential and fun to apply, once you have mastered the basics. To get started, we will briefly cover the subject of intervals, because they are the building blocks of chords in all music. Then we will cover the four types of triads and their inversions. “Inverting” chords can be described as combining the same group of notes in a different order from the bottom to the top.

What Are Chord Inversions?

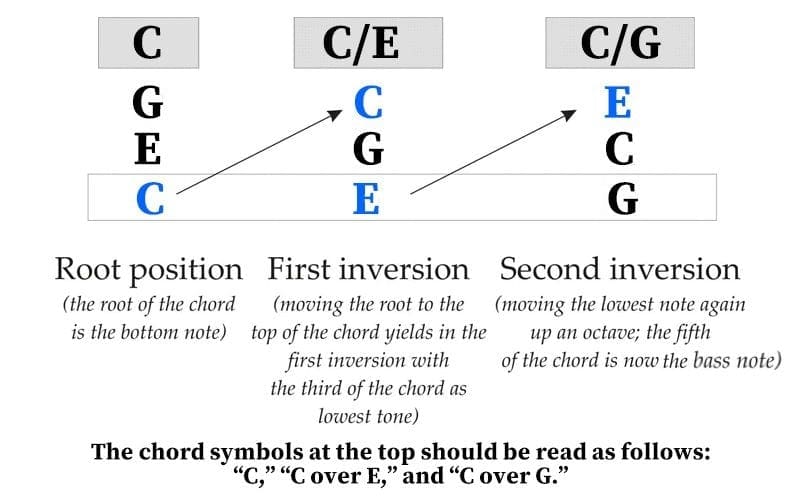

Inversions are chords in which the notes have changed position, and the “tonic” or root of the chord is no longer the bass note. Chances are that you have seen a chord written, “C/E.” Here, the “C” represents a “C Major chord (C – E – G), and the “/E” means that the E note has changed position in the chord to become the bass note. The number of chord inversions is always equal to the number of notes in a given chord.

So, why change the order of the notes? Well, the most compelling reason is the “economy of motion.” When moving from one chord to the next, we can eliminate unnecessary movement with inversions. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it gives writers and performers options in terms of how each chord can be played. Secondly, music sounds better when this knowledge is properly applied. To put it simply, we can choose the best inversion depending on the chord which precedes it, as well as the one that follows it. With practice, these options can be applied by both writers and performers, who can make these choices as they go along.

Now, we will progress on extending chords from triads (three-note chords) to 7th chords (consisting of four notes). We will also cover some practical applications with an example of how to translate this theory into practice using a common, simple chord progression. This will introduce you to the concept of proper voice leading, which is one of the most useful aspects of applying the use of chord inversions.

What Are Intervals And Why Do I Need To Know?

It is necessary to understand the basics of intervals before attempting to tackle chords and their inversions. That is because intervals form the building blocks of chords. An interval is a distance between any two given notes. There are 12 intervals, which span one octave. For those unfamiliar with the word, ‘octave,’ it’s the distance between the note at the beginning and end of the Do-Re-Mi scale.

In scientific terms, you can take any frequency (pitch) and cut it in half, and you have gone down one octave. Take any frequency and double it, now you have gone up one octave. Intervals that are one octave or less are called “simple intervals.” Intervals that are larger than one octave are called compound intervals. Mastering these include ear training, and being able to identify intervals upon hearing them. The rest is pure memorisation. One key factor which can be helpful in memorising these 12 intervals is that, once an ‘octave’ has been reached, the intervals begin to repeat.

3 Categories

The easiest way to fully digest intervals is by tracking three categories:

1. The name of the interval

2. The number of half-steps (also known as semi-tones, the smallest interval in Western culture) of which it is comprised

3. The quality of the interval. There are three possible qualities. They are known as perfect consonances, imperfect consonances and dissonances

These qualities become significant whenever you practice ear training.

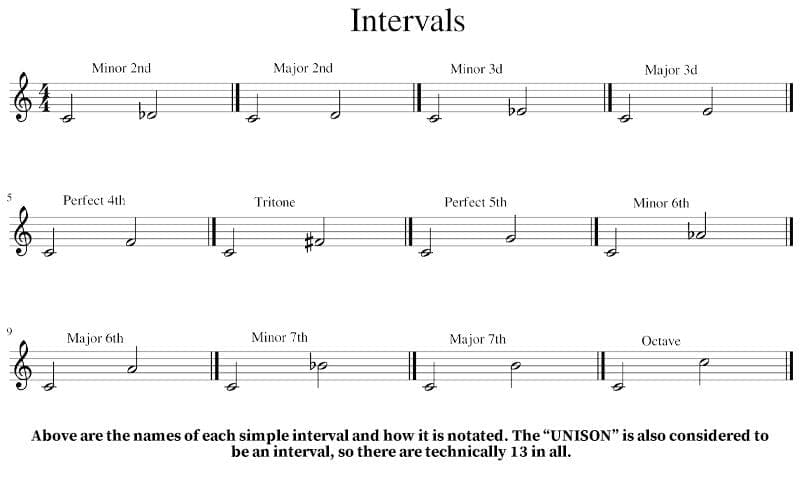

Here is a list of the intervals organised by those three categories:

| INTERVAL NAME | NUMBER OF ½ STEPS (SEMITONES) | INTERVAL QUALITY |

| Unison | 0 | Perfect Consonance |

| Minor 2nd / Half Step / Semitone | 1 | Dissonance |

| Major 2nd / Whole Step / Tone | 2 | Dissonance |

| Minor 3rd | 3 | Imperfect Consonance |

| MAJOR 3RD | 4 | Imperfect Consonance |

| Perfect 4th | 5 | Perfect Consonance |

| AUGMENTED 4TH / Diminished 5th / Tri-Tone | 6 | Dissonance |

| Perfect 5th | 7 | Perfect Consonance |

| Minor 6th | 8 | Imperfect Consonance |

| MAJOR 6TH | 9 | Imperfect Consonance |

| Minor 7th | 10 | Dissonance |

| MAJOR 7TH | 11 | Dissonance |

| Perfect 8th / Octave | 12 | Perfect Consonance |

Note that there is a convention in music whereby Major and Augmented intervals/chords are written in upper case, while minor and diminished intervals/chords are expressed in lower case. This will come in handy when identifying chords with Roman numerals (Nashville numbering system style), because the same convention holds true there.

Points To Clarify

There are three brief points of clarity before we can move on:

1) Here is a definition of the three qualities. A perfect consonance is an interval that sounds pleasing to the ear. Most songs (or sections) will end on one of these because our ears perceive them as a resolution. An imperfect consonance is a transient interval, neither pleasing nor jarring to the ear. They are used to migrate from tension to release and back. Finally, a dissonance is a tension interval which creates unrest and conveys the need for resolution (then enters a perfect consonance).

2) Note that the intervals extend from unison to octave and that alternative names are also listed, where applicable.

3) Finally, there is a symmetry to the qualities which makes them easier to memorise. They can be inverted, just like chords. In other words, when you invert a unison, you add or take away 12 semi-tones. When you invert a perfect 4th (5 semitones above any target note), you have a perfect 5th (7 semitones below that same target root note). Go up by the number of semitones listed, then subtract 12 to invert it! The idea is that a perfect 4th and its inversion (the perfect 5th) both share the same quality – perfect consonance.

Below is a chart that shows how these intervals appear in notation format:

What Are Triads?

Great, so now begins the fun part! We can build chords out of intervals. We will begin with triads. There are four types: Major, Minor, Diminished and Augmented.

Here is another helpful, easy chart for identifying triads:

- Major triad = Major 3rd + minor 3rd

- Minor triad = minor 3rd + Major 3rd

- Diminished triad = minor 3rd + minor 3rd

- Augmented triad = Major 3rd + Major 3rd

What Are Chord Inversions?

So, if we take a C Major scale [ C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C ], then our “tonic” chord would be built from the root in 3rd intervals, so it would include the root, 3rd and 5th notes of the scale, or key. So, that is C-E-G.

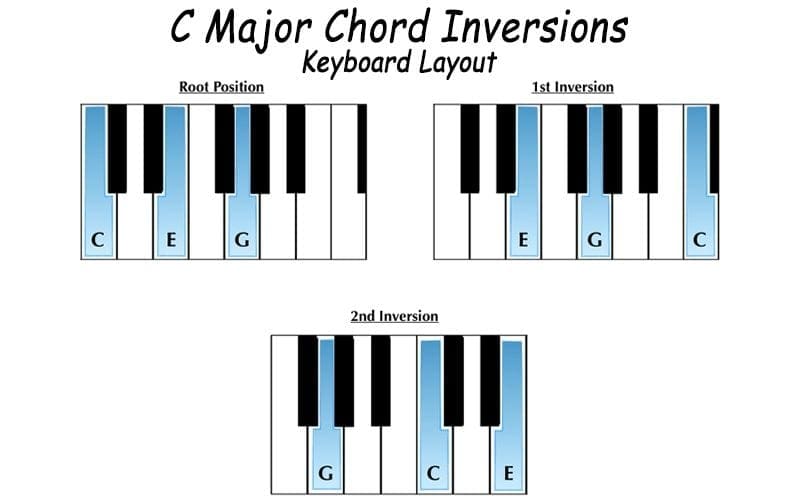

Okay, so let’s invert this tonic chord! We invert a chord by taking the note at the bottom and moving it to the top, or vice-versa. Here is a visual aid below:

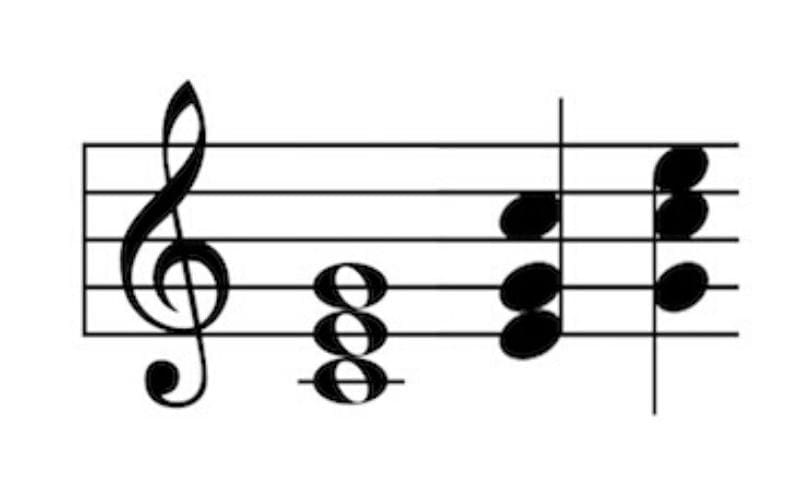

From a notation standpoint, the three positions would look like the following:

The first chord depicted in the illustration above is the C Major chord in its root position – C (root) on the bottom, E in the middle and G on top. The second chord is the first inversion – E on the bottom, G in the middle and C (root) on top. Finally, the third chord here is the second inversion – G on the bottom, C (root) in the middle and E on top.

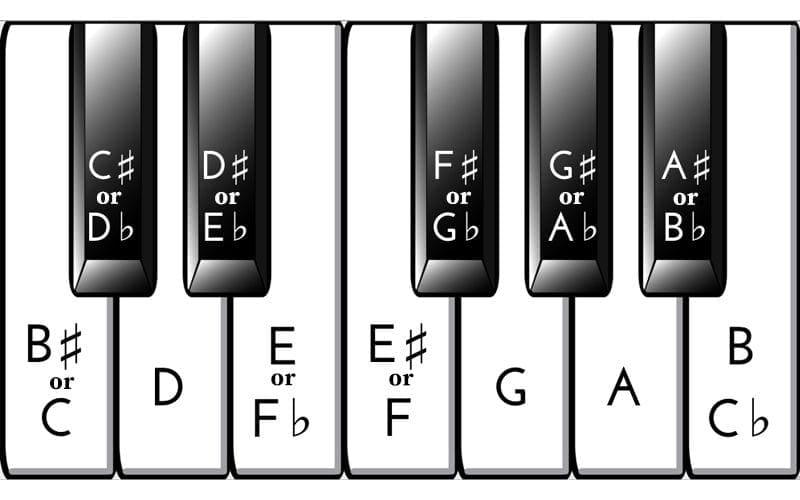

Going back to the list of intervals, one might ask why a “perfect 5th” equals 7 semitones. The answer is that an octave contains 12 semitones, not 8, as one might expect. The prefix, “Oct” usually infers that we were talking about something with 8 increments – an octopus, octagon, etc. Well, an octave contains 12 semitones, but also only contains 8 letter names. So, as musicians, we must account for each of the sharp and flat notes which fall between those letter names.

Enharmonic Equivalents

As you can see below, most of those notes have alternative spellings, which are determined by a song’s key. These alternative spellings are known as, “enharmonic equivalents”. Here is a diagram that depicts all of the notes in an octave on the keyboard, with their alternative spellings:

How Do Chord Inversions Work As They Relate To Piano vs. Guitar?

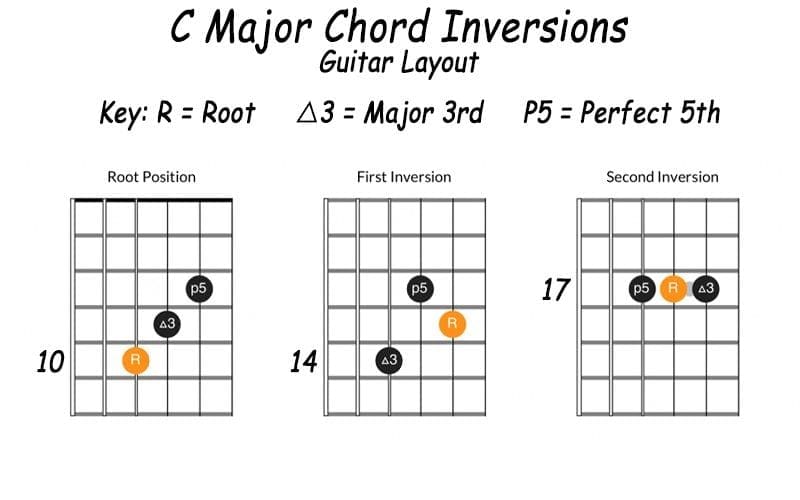

Wondering how chord inversions on the piano or guitar chord can look? Below, you can check out the same C Major chord as it would be inverted on a piano or keyboard vs. how the same process would appear on the neck of a guitar:

One quick point for clarity – the chart below uses a triangle to represent “Major.” That is a commonly used shorthand for musicians and on lead sheets.

What Happens When Chords Are Comprised Of More Than Three Notes?

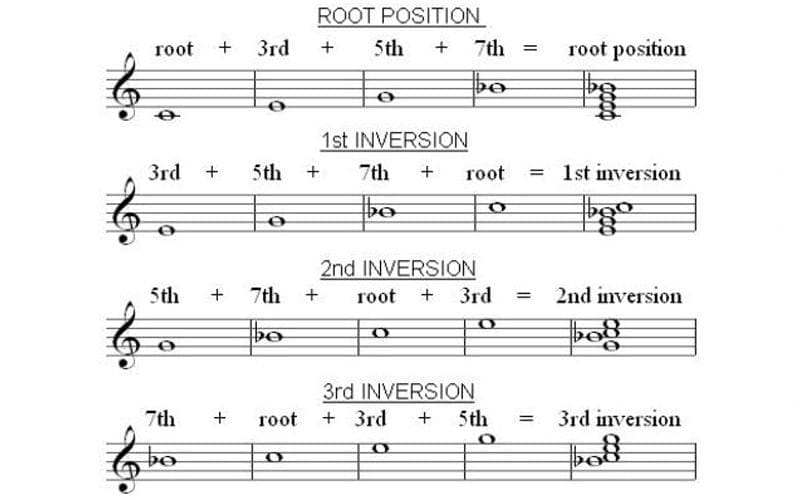

Let’s move forward to the dominant seventh chord, which is a four-note chord. The first noticeable difference from triads is that the number of chord inversions increases with each added chord tone. So, there will be four inversions: root position, 1st inversion, 2nd inversion and 3rd inversion. Below, you can check out the chart which depicts each of the seventh chord inversions (C dominant 7th, or “C7” chord).

The dominant 7th chord is known as a “tension” chord. It is built from the 5th scale degree of a Major scale in 3rd intervals. So, in the case of ‘C dominant 7’, we must first determine what key would have C as its 5th scale degree. The answer can be determined by going backwards in the alphabet (C-B-A-G-F) so C is the 5th scale degree in the key of F Major. The four notes in the C7 chord are C-E-G-Bb.

Inverting Triads And Four Note Chords: How To Apply It

Great – now you have learned the basics of chord inversions, but there has to be some practical application to make it useful. We can use chord inversions when writing or performing by implementing a technique called “voice leading.” Voice leading is the method that we can use to determine which inversion of a chord to write or play, depending upon the surrounding chords in the piece.

For instance, the example below depicts a common chord progression in the key of C Major:

| F | C | G | C |

| IV | I | V | I |

The Roman numeral equivalents, based on scale degree, are written below each of the chord symbols.

With regard to chord functionality within its parent scale, this same progression might also read, “Subdominant (the IV chord), Tonic (I), Dominant (V), Tonic (I).”

You will see how, by applying the “economy of motion” principle, we can invert two of the chords, and implement proper voice leading. This is an essential technique for musicians, especially with regard to improvising. Don’t fret – the Roman Numerals and Arabic chord inversion symbols which follow will be explained in the section below regarding “figured bass”. Here we go:

Figured Bass

Now, let’s take a look at the “figured bass” part of the equation. You have learned how to take any of the four types of triad and invert it. This triad in first inversion will be an essential technique for any songwriter or performer because it reveals options for the range where each chord will be played. The choice will depend upon the musical context, but the economy of motion is the key factor. There will be more illustrations below to clarify that point.

Roman Numerals And Arabic Numbers

The Nashville Number System was actually derived from another Roman numeral system used during the Baroque period (approximately 1600 to 1750). Using this system, a composer could write chord symbols which would specify a chord’s intended inversion. This is done by using Arabic numbers written after the Roman numerals. This indicates the inversion by its interval, or distance, from the bass note. The Roman numerals themselves are used to number the chords of any particular key, based on scale degrees. For example, the key of C Major would be broken down as follows:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii | I |

If we were to count the intervals in the chords above, we would note the following order:

I=Major, ii=minor, iii=minor, IV=Major, V=Major, vi=minor, vii0=diminished (that is what the little circle represents) and back to I=Major. This is a key formula for any major key.

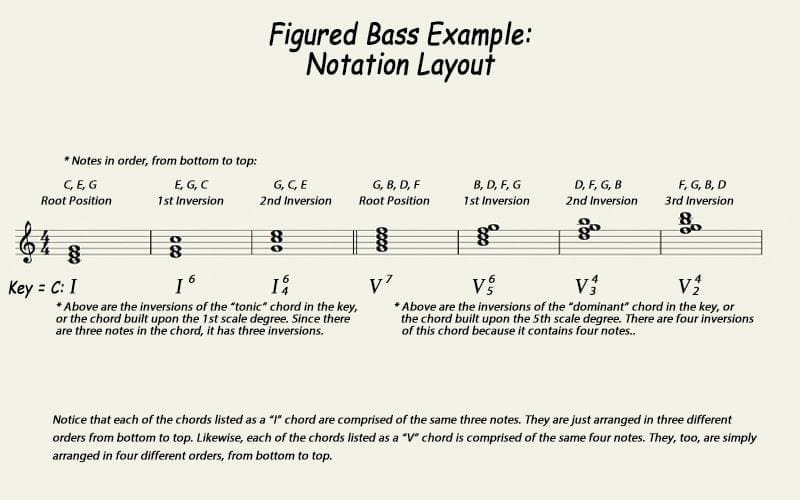

Chord Inversions In Numerals

The part about the upper and lower case still holds true here. When these Roman numerals are followed with Arabic numbers, it tells what inversion we should play. Those numbers tell us where the root is relative to the chord’s bass note. So, a C chord in root position would be notated as ‘I’. In 1st inversion, it would be I6. ‘I’ tells us that it’s a C (tonic) chord, and the “6” tells us that the root is a 6th (minor 6th, in this case) interval above the bass note. The C is a minor 6th interval above the bass note, which is E. So, the ‘I6’ is the Nashville notation equivalent of C/E.

Likewise, the second inversion of any diatonic chord may be depicted as I 6/4. In that instance, the root is a 6th interval up from the bass note. The next chord tone down is a 4th interval above the bass note. The following chart shows how triads are notated using the Nashville Number System:

In the example above, the Arabic number on top represents the interval between the root and the bass note. The other Arabic number represents the next chord tone down and its interval relative to the bass note.

Chord Inversions: Summary

So, now you have made some great gains in the ability to utilise intervals, triads and their inversions, as well as four-note (7th) chords and their inversions. We also discussed the principle of “economy of motion,” and how integral it is to both writing and performing music. It makes chords easier to play by minimising movement, yet making the harmonic changes necessary to add rich harmonic content to the music, from the highest to the lowest notes. That is what engages your listeners. Avoiding great leaps when changing chords makes music sound better.

We touched upon how helpful it could be in terms of improvisation, especially once you have mastered the technique of inverting chords to the point at which you can apply it on the fly.

As previously mentioned, one of the key factors in improving these skills is ear training. There is a website called Good-Ear.com, which can assist you in that regard. Finally, we discussed how figured bass has been a prevalent fixture, especially in the Nashville music scene. When chord changes are indicated with Roman numerals, it is usually done so the reader can quickly transpose the song into whatever key suits a particular vocalist. The accompanying Arabic numbers, or figured bass, are used simply to tell the performer what chord inversion to play!

For more information about harmony, check out our article. You can also learn about other helpful techniques such as arpeggios.